Good News! You’re Only a Creature

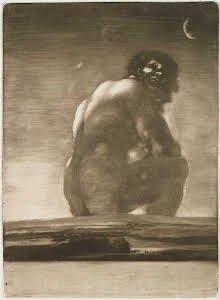

Seated Giant, Francisco Goya (1818)

This year, the Octet Collaborative is using this essay space to explore the question underneath so many of the questions that drive our work at MIT: what does it mean to be human? Among the topics that we’ll explore this year will be three core Christian doctrines and how they relate to our humanity: the doctrines of creation, the incarnation, and the resurrection of the dead. All three are found in the foundational creeds of our faith, and all three, we will see, are essential to an understanding of what it means for humans to flourish. Today, we begin with the doctrine of creation. Put another way, we’ll explore what it means to say that to be human is to be a creature.

Existence is a gift

The doctrine of creation is about God before it is about creatures. God is the creator: this means that he is utterly unlike creation in that he and he alone exists necessarily, of himself. All other things - seen and unseen - are brought into being and sustained in being by him. The doctrine of creation, distinct from a Christian account of origins, answers the question of why there is something rather than nothing, not the question of how things came to be what and how they are. On a Christian account, creation is not a necessary emanation from God (which would make creation part of God, or would mean that God is somehow completed in creation): it is the utterly gratuitous and free act of a triune God who exists in perfection, even in perfect relationship, in and of himself.

The first implication of the doctrine of creation with bearings on what it means to be human, then, is this: existence is a gift. It is pure gift - not owed to us by God, not dependent on anything from us whatsoever. God creates ex nihilo, from nothing, and to be his creature is to receive the gift of existence before we can receive anything else.

It is good to be a creature

Existence is a gift, but that’s not where the gift ends. Genesis 1 says, repeatedly, that creation is good, and even very good. This simple statement has elicited resistance for centuries: early Christians pushed back against gnostics who denied the goodness of the material world, while today, transhumanists point us to a future where technology will deliver us from the limitations of physical embodiment.

The goodness of creation has to be held in tension with the travails of a fallen world. Not everything in creation is good: death and disease, thorns and thistles, loneliness and grief and cruelty: these are not the way things are supposed to be. But it must be maintained that the fall of creation doesn’t change the essential goodness of creation, because it doesn’t change what creation is. “Sin is not creative,” wrote the theologian Karl Barth: sin can distort and corrupt, but God alone is the creator, and there is none beside him. There is an important implication of this for our understanding of humanity: as we explored in a previous essay, the Bible grounds human dignity in the fact that humanity is made in God’s image, and crucially, sin has not changed that fact. Even after the fall, the Bible insists that every human being bears the image of God (Genesis 9:6, James 3:9).

We can affirm the goodness of creation even as we lament and labor, by grace, to subdue the effects of the fall (we’ll explore that aspect of our vocation more in a future essay). And this means affirming the goodness of the limitations that are built into material creation. We are not made to be everywhere at once; we are not made to sustain unlimited relationships or endeavors.

Technology, as the transhumanists and may others understand it, promises to overcome the limitations of being a creature; on a Christian understanding, these limitations are themselves part of God’s very good creation - they are part of the gift of being a creature. This suggests that instead of sinking our hope into the power of technology to overcome creaturely limitations, we should be asking ourselves what it means to align ourselves with them, to run “with the grain of the universe,” as Stanley Hauerwas said. What does it mean to receive not only our existence, but the goodness of creaturely limitations, as a gift?

Receiving the gift

Theologian Kelly Kapic has recently published a wonderful book on this very topic, entitled You’re Only Human: How Your Limits Reflect God’s Design and Why That’s Good News. In his final chapter, he offers the following four ways to receive the gift of being a creature. To be clear, what follows is my own reflections on these four points of wisdom, and is not meant to be a summary of Kapic’s chapter - for that, I hope you’ll consider buying his book!

Embrace the rhythms and seasons of life

My wife and I have differing opinions on the merits of living in New England. I love living in a place with true seasons; she wonders why we ever left California, which seems to enjoy one perfect season all year long. We can leave that debate for another day (and have it somewhere other than the internet), but I do believe that the annual cycle of seasons offers us wisdom for being a creature. Summer and winter are not the same; there is a season for nature to grow and flourish and a season for it to pull back and lie dormant. The book of Ecclesiastes suggests that the same applies to our lives: there is “a time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up what is planted… a time to weep, and a time to laugh…” (Ecclesiastes 3). The season of childhood is different from the season of maturity. Those of us called into marriage and parenting will find that these seasons bring with them unique joys and burdens, which rightly displace other endeavors. In his letter to the Corinthians, Paul observes that those not called to marry remain free for greater devotion to serve the family of the church; even so, all of us will be called into seasons of more intense demands, caring for friends, roommates, aging parents, projects at work and in our civic duties - and other seasons, when we are freed up to lay those burdens down and pass them on to others. It takes wisdom to know which is which, but the key point is this: you are not made to do all things, all the time.

Recognize vulnerability

In his excellent short book Strong and Weak, Andy Crouch points out that we instinctively see authority and vulnerability as opposite ends of a one-dimensional spectrum, with power and domination at one end and suffering at the other. In a brilliant move, he asks - what if instead, we see them as axes on a two-dimensional plane? Domination and suffering are still there - the former when we have high authority without vulnerability, and the latter when we are highly vulnerable with no authority. But there is also the possibility of exercising authority and being vulnerable at the same time, which Crouch calls flourishing. This drives against our every instinct: we do not want to be vulnerable! But life teaches us how wise it is for limited creatures to embrace their vulnerability, even as they act with authority. The best parents are those who provide strong authority for the sake of their children, even as they are emotionally vulnerable with them, modeling repentance when they inevitably make mistakes. The best professors and corporate leaders are those who lead with expertise, but at the same time demonstrate the intellectual humility to admit when they don’t know the answer, and can receive novel solutions from students and employees. And as Crouch points out, the highest demonstration of authority and vulnerability working in concert is the life of our Lord Jesus, who exercised incomparable authority over the powers of the world, flesh, and devil, but who lived in utter dependence on his heavenly father and chose to be vulnerable to death, for us and our salvation. We’ll expand more on this in a future essay, when we consider being human in light of the incarnation.

Express lament, cultivate gratitude

A future essay will also delve more deeply into the difference between receiving the gift of creaturely limitations, versus hoping for and even joining God in the restoration of all that is fallen, on the basis of his divine work of resurrection. For now, we will simply point to the wisdom of the Psalms for life in a fallen world. No one praised God for his goodness and his blessings the way David did. No one cried out “How long?” the way he did in the face of cruelty, oppression, and injustice. No one else lamented the darkness, loneliness, and silence that visits us when we experience the dark night of the soul. The fact that we find every human emotion expressed in the form of prayer in the Psalms, and then taken up by Jesus during his own lifetime, is a powerful reason for us to soak in them ourselves, in order cultivate our own expressions of gratitude and lament, and lay them at God’s feet. Gratitude and lament are both forms of praise: we give thanks to the one who creates and sustains our lives, and we cry out to the only one whose steadfast love and power are sufficient to restore what has been lost.

Rest: honor sleep and sabbath

If the first point we drew from Kapic was to embrace seasons, we should end by pointing out the most important cycle God has given his people: six days of labor, one of rest (you can read here how this gift is woven into the name of the Octet Collaborative!). A seven day cycle isn’t something drawn from nature; it doesn’t line up with the sun or the moon or the annual cycle of seasons. It is simply a gift, reminding us (in Exodus 20) that we are made in the image of a God who created all things in six days and then finished his work by resting on the seventh, and (in Deuteronomy 5) that we have been set free from all forms of slavery and oppression. We put down our work to recognize all the ways that we depend on God as creatures, to do what we cannot. We rest in him on the first day of the week, before we have accomplished anything, because sabbath rest is a gift we receive, not a reward that we earn. Each night we sleep, trusting in God to be at work while we are not, and to wake us up to a new day, full of new mercies and new callings. Our bodies are created in such a way that if they do not rest, they break down. Though we might not feel it as acutely, our souls inevitably break down without regular pausing to rest and worship God. Receiving the gift of the sabbath is perhaps the most countercultural, and for that reason the hardest and most important, way that we receive the gift of creaturely limitations.

Technology and the Gift of Creaturely Limitations

There is more to say, and we will develop these themes further over the course of this year when we consider the incarnation and the resurrection. For now, one last set of questions for the work of MIT in particular: what does it mean to receive the gift of creaturely limitations in our work as scientists and engineers, as we develop, implement, and use technology? What would it mean for technology to help us to engage more with the goodness of the created world, instead of withdrawing from it? What would it mean for it to promote deeper engagement in relationships with other humans, without smoothing over the frictions and inefficiencies they bring? How could scientists and engineers, in conversation with theology and other disciplines, distinguish between fallenness to be overcome versus creaturely limitations to be received, and then lead humanity in developing technology that does both? These are huge questions, and we at the Octet Collaborative cannot find the words to express our gratitude that we get to explore them in community at MIT. We look forward to future collaborations and conversations in the years to come!