Grace is in the Wilderness

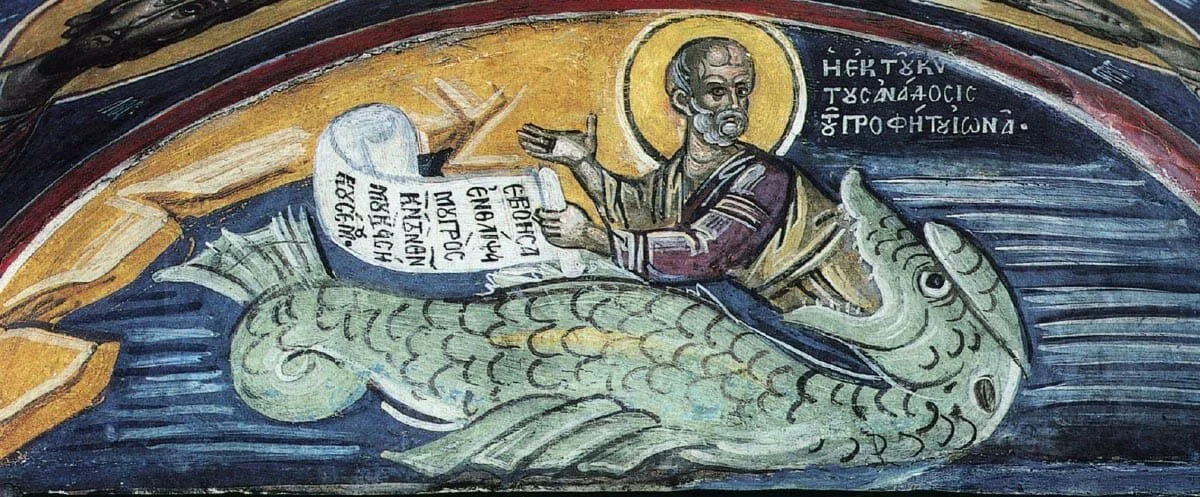

FRESCO OF THE HOLY PROPHET JONAH

“What does it mean to be human” is the question we’re continuing to explore at Octet this year, and I believe a central component of the human experience is suffering. This is not to suggest that we were specifically designed for the purpose of experiencing suffering, but it is nevertheless an inevitable and distressing reality that pervades our lives. So what should we think about it? What can we do about it? Is there more to suffering than the stings and wounds it brings?

Pop culture often defaults to idioms like, “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” or “No pain, no gain,” as explanations to appropriate suffering as the means by which one develops into a more capable person, thereby giving it a positive quality that then enables one to accept it more readily. While there is a degree of truth in these sentiments, thankfully, the Bible has much more to say about it that should bring a sense of deeper security. In what follows, I hope to encourage and empower the MIT community by offering a short exploration of a redemptive quality from suffering.

Wilderness: Chaos, Dangerous Animals, & Demons

To begin, I’d like to explore one of the most familiar symbols of suffering in the Bible: the wilderness. It should be noted at the outset that the wilderness is loaded with varying theological significance due to its various definitions and functions in different contexts, and a comprehensive undertaking will not be the aim of this space. Instead, we will focus on one particular angle: the “wilderness” as an often-despised space that, paradoxically, also serves as the setting for momentous divine revelations.

In the Bible, the wilderness is often understood as the uninhabitable territory where chaos, dangerous wild animals, and supposedly, demons abound. For example, in Deuteronomy 32:10 it is described as a “howling waste of the wilderness.” The Hebrew term tohu (תהו), which in this verse is translated as “waste,” is the same term that is used to describe the “formless” earth in Genesis 1:2. The key idea to note about the wilderness being tohu is that it is chaotic–there is no order, it is an uninhabitable space, and thereby it poses a threat to human settlement and life, much like the primordial waters that dominated before the creation of the world. As for dangerous wild animals, Deuteronomy 8:15 mentions that the “terrifying wilderness” contains “fiery serpents and scorpions” that pose a threat to human flourishing. And passages such as Leviticus 16 with Azazel,[1] Luke 8:29, and Matthew 12:43/Luke 11:24 indicate the common presence of demons in the wilderness. All these points serve to underscore the larger point that the wilderness is often viewed as a hostile territory that poses danger and suffering to mankind. It can be seen as the space that no one desires to enter, let alone dwell in for an extended period of time.

The analogous experience in our context may look something like our workplaces. Some labs may feel chaotic due to the precarious circumstances of funding, shifts in roles and positions as colleagues come and go, and the pounding waves of work that weigh down on us to meet deadlines. Perhaps, toxic work environments may resemble the ancient wilderness experience because of the caustic remarks that co-workers throw around—and we all know that words can “sting like a bee” (or fiery serpents and scorpions). And sometimes, our greatest wilderness is not bound to a space external to us—it may very well be in our own minds. When we trap ourselves in the self-denigrating voices of doubts, demoralizing comments from others, or revert to our tendency to compare ourselves to an unhealthy level of perfection, we are in some way wrestling with demonic voices. While it is clear that the wilderness was a place of hardship for the ancient Israelites—just as our modern wilderness experiences can be distressing for us—it is, however, also the very place where momentous divine revelations occur. A few biblical examples may further demonstrate this notion.

Whisper of Hope, amid the Roar of Despair

The wilderness was the place where God repeatedly demonstrated his power and providence to the Israelites—leading them by a pillar of cloud and fire (Exod 13:21–22), raining down manna (Exod 16), and commanding water to flow from a rock (Exod 17)—even when they were surrounded by nothing but barren wastelands. That is to say, the wilderness—symbolizing the all-too-pervasive experience of suffering—is not reducible to mere hostility working to demoralize its victim. Rather, it also bears the marks of miracles, wonders, and divine revelations, drawing the beholder into awe and wonder. The Israelites encountered this not in ideal conditions, but in the wilderness—the very place we most naturally seek to avoid.

God appeared before Moses and the Israelites on top of Mt. Sinai (in the wilderness) to establish a covenant with them—a covenant that would decisively establish Israel, above others (Ex 19:5–6), as God’s people. Despite the instability and dangers that the wilderness imposed on the Israelites, for whatever mysterious reason, it was here—and not in a dazzling, Edenic setting—that God chose to reveal his glorious presence to invite people into a unique relationship with him. God also appeared to Elijah on a mountain (in the wilderness) during a time when he despaired greatly. Once again, the key point being God revealing himself to a suffering victim in the moment of distress in his wilderness–the very place we naturally seek to avoid.

Some scholars have noted the connections between the wilderness and the sea, for their shared traits of being chaotic, uninhabitable, and thereby destructive for human flourishing. Robert Barry Leal calls it the “wet wilderness of the sea.”[2] Using this association, Leal helpfully identifies the Jonah narrative as another example that connects divine revelation with the (wet) wilderness. It was Jonah’s experience in the belly of a large fish that deepened his encounter with God: “As my life was ebbing away, I remembered the Lord; and my prayer came to you, into your holy temple. (Jonah 2:7)”[3] In other words, a decisive turning point in the Jonah narrative occurs in the “wet” wilderness, wherein a divine encounter takes place amid the adverse circumstances.

Lastly, another example of the “wet wilderness of the sea” is found in Mark 4:35–41. As the winds and waves were beating against the disciples’ boat, Jesus awoke and rebuked the aggressive elements, leaving the disciples in great fear (Mk 4:41). What deserves our attention is that the very elements that posed a threat to end human life—that is, the disciples’ immediate suffering from tempestuous winds and waves—were the very elements Jesus employed to deepen his disciples’ understanding of him. Without them, the greater opportunity of experiencing deeper revelation, awe, and reverence would be absent. Here, we can see that the “wet wilderness”—though not ideal for the safety of human life—was the ideal condition in which the disciples were able to witness extraordinary events. Our survey of biblical examples, of course, does not mean that God’s revelations and wonders are limited solely to moments of suffering. But it does highlight an important facet of suffering that can easily be overlooked when the pain clouds our vision.

Today, suffering is rarely spoken of in positive terms, and understandably so. I’ve never met anyone who delights in their pain to the point of wishing to prolong it. Rather, it’s something we’re inclined to move past as quickly as possible. Yet instead of relying on the exhausting task of resisting and evading it time and again, I have sought to offer what I believe is a more rewarding approach—and, in turn, a lighter burden. Thus far, we have considered what the significance of suffering may be, by exploring how the Bible presents its understanding of it, in the form of the wilderness. Select passages reveal that we should not restrict our understanding of the wilderness (or, our experiences of suffering) to mere forces with the ultimate telos of inducing harm. While the hostile element is real and concerning, there is arguably a greater reality that the scriptures want us to notice in our trying times: the invaluable experience of witnessing the divine—an experience that is truly life-changing. So, rather than defaulting immediately to search for the quickest way out of the discomfort, perhaps the more appropriate action is to pray and ask, “LORD, where are you in all this? And what is it that you want to show me through this?” We are made to experience God—to live with him, be mesmerized by his glory, and worship him, even in our suffering.

In times of distress, may we, as Christians at MIT, echo the psalmist’s prayer in Psalm 77, summarized in the following words:

“I cry aloud to God,

aloud to God, and he will hear me.

In the day of my trouble I seek the LORD;

in the night my hand is stretched out without wearying…

I will remember the deeds of the LORD;

yes, I will remember your wonders of old.

I will ponder all your work,

and meditate on your mighty deeds.

Your way, O God, is holy.

What God is great like our God?”

-Psalm 77:1–2a, 11–13

REFERENCES

Hastings, James (1963) Dictionary of the Bible. (2nd Edition) Edinburgh, T&T Clark.

Leal, Robert Barry. 2004. Wilderness in the Bible : Toward a Theology of Wilderness. New York: P. Lang.

[1] See entry for “Azazel” in Hastings, Dictionary of the Bible, 81. “In the book of Enoch, “Azazel appears as the prince of fallen angels, the offspring of the unions described in Gn 6:1ff.”

[2] See Leal, Robert Barry. 2004. Wilderness in the Bible : Toward a Theology of Wilderness. New York: P. Lang, 107.

[3] Ibid., 107.