Got Virtue?

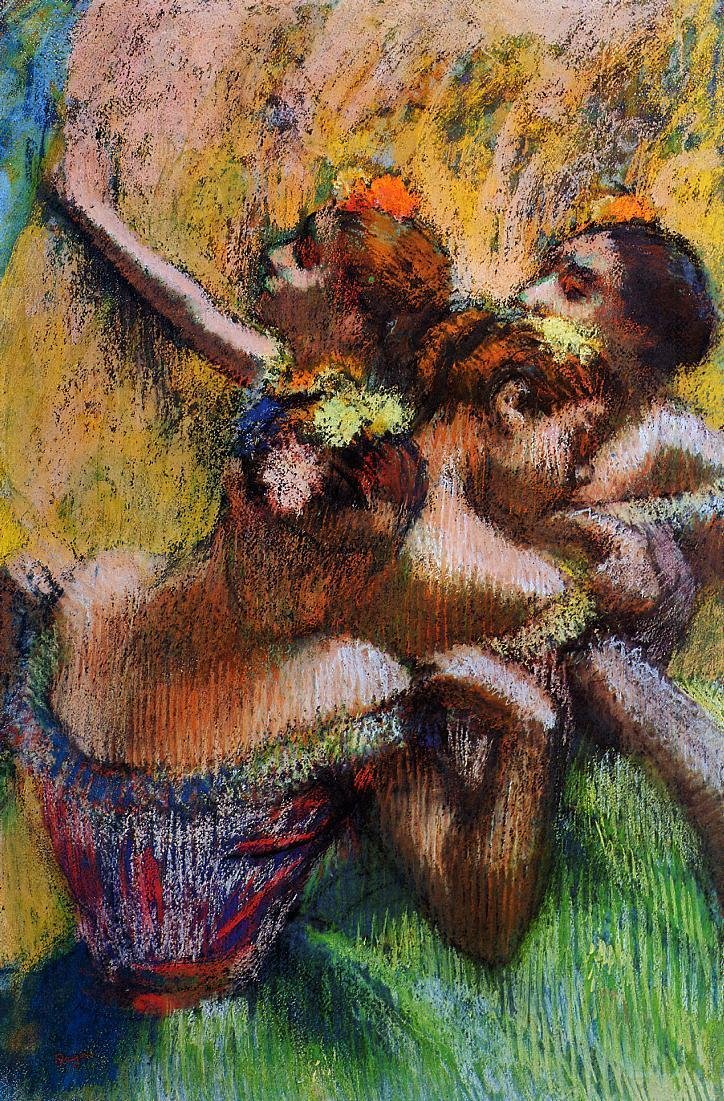

Four Dancers, Edgar Degas (1902, French)

In March of 2023, a speaker at MIT argued that in a the context of the university, our challenge is to be about the intellectual virtues, not the moral virtues.

The context for that statement was an event hosted by the Institute kicking off a series called Dialogues Across Difference - “a series of guest lectures and campus conversations to encourage community members to speak openly and honestly about freedom of expression, race, meritocracy, and the intersections and potential conflicts among these issues.” The speaker had just been asked - what about forgiveness? When we hear someone say something that we find not only wrong, but offensive, perhaps deeply hurtful, what role should forgiveness play in our response? The speaker’s response was to say that although forgiveness is incredibly important in all sorts of human interaction, it’s irrelevant as such to the university context, where we should restrict ourselves to intellectual pursuits.

This year, the Octet Collaborative intends to use this essay space to explore the role of virtue in the life of the university, and in particular to explore how human flourishing within the university depends on the cultivation of all the virtues - intellectual and moral, as an integrated whole, in service to the university’s vocation of forming persons. We’ll have the opportunity to explore specific virtues, with the help of some guest essayists from among our local partners. In this introductory essay, I want to talk about what we mean by virtue, why they can’t be divided into moral and intellectual, and what their pursuit would look like at MIT.

Virtues, Jennifer Herdt writes, “are stable dispositions that enable an agent to respond and act well” to a given situation. [1] In her book Intelligent Virtue, Julia Annas writes that “a virtue is a disposition of character to act reliably, not a passing mood or an attitude. Nor is it a trait or a mere disposition to perform acts that have been independently labeled as virtuous.” [2]

The reason that moral virtues and intellectual virtues can’t be split apart is because the person can’t be split apart. Different situations call for different virtues - courage, wisdom, justice, temperance - but it is the same person, with a single and undivided character, called upon to respond to each one. There’s not a courageous part of me or a wise part of me that can be developed in isolation and deployed when necessary - much less a “moral” and an “intellectual” self that exist independently of one another. If the university is about the formation of persons then it is about the project of building virtue, full stop.

That last sentence begs an important question, however - is the university about the formation of persons? In the early 1990s, Mark Schwehn argued in a slender volume called Exiles from Eden that, under the influence of Max Weber and like-minded sociologists and pedagogical theorists, the aim of the university had shifted from the formation of persons engaged in the life of the mind, to the production of knowledge. [3] If this is true, it certainly goes a long way toward explaining why faculty at top universities are judged almost exclusively according to their research output, and come to see the laborious task of teaching as little more than a distraction from their real jobs! And perhaps the best evidence for the truth of Schwehn’s diagnosis is how rapidly our knowledge seems to be outpacing our capacity to use it wisely, in fields as diverse as computing and artificial intelligence, biotechnology, finance and economics, and the energy infrastructure that powers our world. Today more than ever, it seems, we can resonate with the words of the book of Job 28: “Surely there is a mine for silver, and a place for gold that they refine… [and, we could add, labs for innovation, and capital markets to funnel resources to the most profitable enterprises]… But where shall wisdom be found?”

What would it look like for universities like MIT truly to pursue wisdom - and courage, justice, and temperance, faith, hope, and love - as interconnected virtues? What would it mean to return to the older vocation of forming persons engaged in the life of the mind - persons, note, who are more than their minds, and who therefore engage their souls, spirits, and bodies even in their intellectual pursuits? The nature of virtue indicates that it wouldn’t so much mean changing the content of the curriculum as it would adopting different pedagogical practices that would put the rhythms of academic life to use instilling habits conducive to the character necessary to sustain the scholarly vocation.

Virtues are stable dispositions of character in the same sense that muscle memory provides a stable capacity to an gymnast to hit the same dismount every time, or allows a fluent speaker of a language to converse as easily as breathing, or gives a musician the ability to play a piece of music while applying their mind to the pathos with which they play or to improvisation, rather than the the mechanics of the piece itself. Virtue is “second nature,” a phrase which is useful for reminding us that it is not innate (not simply “nature”), but acquired - but once acquired, becomes the most natural thing in the world. Annas writes, “a disposition has to be acquired by habituation, but a virtue is not a matter of being habituated to routine. It expresses the kind of habituation that a skill does, one in which the agent becomes more intelligent in performance rather than routinized.” [4] When it comes to virtue, we simply learn by doing. The way to become a just person is to act justly; the way to become courageous is to do courageous things. This is why the acquisition of virtue requires being embedded in a community of persons who love and model the good toward which the virtues are oriented, without which a person seeking to acquire virtue would have no starting point.

One of the mistakes we can make about virtue is to think that an action is more virtuous if it requires more effort. Consider two sons contemplating giving their mother a phone call on her birthday (and for the sake of argument, suppose both have an equally good, loving relationship with their mother). For one, the call is natural, easy. The other would really rather not make the call, and has to argue himself into doing so - it is, after all, the right thing to do. We have a tendency to think that what the second son has done is more admirable than the first, precisely because he had to put more effort into it - but this has it exactly backwards. While both sons may be motivated by exactly the same love for their mother and sense of duty as sons, only the first has had those motivations work themselves into his character, so that acting on that love and duty has become “second nature,” a part of who he is (of course, the good news for the second is that by making the call that he doesn’t want to make, he’s actually doing the very thing which, over time and with repetition, will build the same character).

How does this apply in the university context? What are the habits of life that can build the virtues necessary to engage the life of the mind, for the common good? The answer to this may vary with specific virtues and applications, but let’s consider this question under the three aims that the Octet Collaborative has put at the core of its mission: hospitality, wisdom, and wonder.

Hospitality, love of the stranger (intellectual or otherwise) requires repeated exposure to those who are not like us, with consistent devotion to their well-being, even in disagreement. We must repeatedly expose ourselves to others who are not like us, differing in their perspectives and opinions, allowing our own positions to be challenged even as we generously contend for our own beliefs. We must be willing to be offended - and, yes, we will have to practice plenty of repentance and forgiveness along the way.

Wisdom - where is it to be found, after all? The Proverbs offer an answer that seems less than helpful at first: “The beginning of wisdom is this: Get wisdom, and whatever you get, get insight.” (Proverbs 4:7) So… if you want wisdom, get wisdom. But maybe this only seems circular because we’ve been so trained to identify wisdom with knowledge, or, worse, with information. Wisdom is more than data, which can be stored in the cloud and uploaded to a device in my pocket. Wisdom is a virtue, and a virtue is a stable disposition of character in a person. And if that’s true, then what the Proverbs are saying is - if you would be wise, find wise people, and watch how they do it. Find teachers; find mentors; find people who have gone before you in life and can tell you how it goes, including the mistakes they’ve made along the way.

Wonder and awe are not hard to encounter at an institution like MIT. Its students, faculty, and staff explore the deepest mysteries of the universe from the farthest galaxies to subatomic structures. Less well known is the excellence of MIT’s humanities departments: music, drama, literature, philosophy. One of the key insights delivered by John Henry Newman in his classic work “The Idea of the University” is that the unity of the university derives from understanding that all of these different fields of study are really examining one thing: God’s creation. When we remember that, we experience awe and wonder before the grandeur of creation and its Creator. This experience generates the virtue of humility, as we locate ourselves in something far larger than ourselves and are pointed to one to whom we can direct our thanks and praise.

Virtue is a stable disposition of character, which is something that inheres in an individual - but it is acquired in community. If the university is about formation, then it must be a community ordered toward virtue - one in which students find mentors to imitate and in which habits are ordered around the right common objects of love. Jennifer Herdt writes, “The virtues are not inborn, but neither can they simply be taught. Virtues are like skills in that neither is innate, and both are acquired through a kind of learning by doing that is not a mere matter of copying or repetition but requires understanding and a capacity for improvisation in the context of new situations. Emulation of a virtuous exemplar is never simply a matter of rote imitation but involves a deepening grasp, affective as well as cognitive, of what is worth doing and being and why.” The Octet Collaborative is dedicated to coming alongside MIT in an effort to build a community dedicated to human flourishing, one which facilitates precisely this dynamic of modeling and mentoring, for the common good.

[1] Jennifer Herdt, “Theology Brief: The Virtues,” from the Global Faculty Initiative, available at https://www.facultyinitiative.net/content_item/389

[2] Julia Annas, Intelligent Virtue (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2011), p. 4. Note that I’m here distilling the traditional understanding of virtue that has come down through such thinkers as Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas; the works cited in this essay by Jennifer Herdt and Julia Annas provide accessible but nevertheless constructive contemporary treatments of this tradition.

[3] Mark Schwehn, Exiles from Eden (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1992). Interestingly, MIT’s own mission statement contains a nod toward both: “The mission of MIT is to advance knowledge and educate students in science, technology, and other areas of scholarship that will best serve the nation and the world in the 21st century.”

[4] The title of Annas’ book, Intelligent Virtue, is derived from the fact that virtue is not like a routine, something that we do so often that we can do it “without thinking,” or “on auto-pilot,” as when a commuter arrives at home with practically no memory of the drive home. Rather, it is more like a practical skill, in which the practitioner can engage more and more varied facets of her intelligence as it becomes second nature - again, think of the expert musician who no longer has to think about the mechanics of finger placement but whose mind remains fully engaged and can think more deeply of how to interpret the piece before her on a given occasion.